Masks

Masks have become so important to our safety and survival during this pandemic, and an added and essential accessory to our clothing wardrobes. Marketed as functional and fashionable in some cases in various materials and price points, they have become a way to express collective caring for our neighbors and others in the public spaces we move in.

In my last post, I eluded to recent acts of solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement as a mask of sorts, like the ones we put on to present ourselves to the world to represent how we want others to see us. On social media in the world of witty slogans and smart graphic images, you can pretty much be anybody, authentic or not.

There have been discussions from psychologists and others about why we get so tired during endless zoom meetings. Perhaps it is the effort to maintain the face that we have constructed for public and professional circles we interact with and get tired of holding. Let’s be real: we are different people in different circumstances.

I will confess, I enjoy a sense of freedom when I am in an all-Black space, and even more when that space acknowledges my right to be queer. I can speak in an easy shorthand. In all-Black spaces I can be many selves and all of them for the most part are ok, unless I encounter some homophobic negroes or those holding a rigid generational divide.

Although I am wedded less and less to presenting any sort of mask anywhere the older I get, I will confess that I am not beyond performance when I am around those not familiar with the many manifestations and beauty of blackness. Sometimes I am even more Black.

I had a significant revelation in my second jaunt in graduate school starting in the early aughts. I worked as a self-taught graphic designer and art director in my young professional life, at a time when the barriers to entry were not so expensive. I do not have an undergraduate degree, and I taught myself design as I was raising my son as a single mom. Being schooled by my family that being an overachiever was a prerequisite to succeeding as a person of color, I did obtain two graduate degrees: one, in business that I went for to elevate my design practice in the 1990s, and a MFA, wanting to expand my practice into three and four-dimensional art and design, as well curatorial training and studies in art history, theory and criticism.

I studied Furniture Design at the Rhode Island School of Design, known as RISD, and completed an additional 36 credits (the equivalent of an MA) for a concentration in art history, theory and criticism at the school. I figured I wasn’t going to go to school again, so I went for it. The furniture design curriculum was challenging but set. For the concentration, I had to invent my own curriculum. I was fortunate to find support from a few generous professors that guided me in independent research. This was not always easy, as I had to find many of my own references outside the bounds the school.

I enjoyed a survey course in Art Criticism and Critical Theory from 1945 to the Present taught by the independent curator and writer Debra Bricker Balken during my first year. I got a taste of the few Black critics she included and wanted more. RISD did not offer a course entirely devoted to Black art criticism.

With only token representation in anthologies and readers, I found no comprehensive surveys of art criticism by Black critics. Searching in course descriptions in nearby New England schools such as Brown, Yale and Harvard, I thought for sure I would find a related course I might be able to weasel my way into. No such luck. Yes, for literature and music. Yes, for surveys of African American art, but nothing specific to surveys of critical interrogations of Black visual art by Black writers, scholars and intellectuals.

After sharing my disappointment with an advisor, she said, “You will just have to do that research to create a basis for the course you envision yourself.” So, I did. I collected various texts and historic material from the early 20th-century pioneering criticism of Freeman H. M. Murray, to the Post-Black era that could be used as a foundation to construct the course, which I eventually taught at my first tenure-track position at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

During my research, I remember reading scholar Kellie Jones, who suggested when writing about the photographer Lorna Simpson, that her non-erotic portrayals of Black women create a context where the gaze becomes a contemplative exercise. In this case, this inspired me to contemplate the invisibility and marginality of the Black voice in critical art discourse and academia.

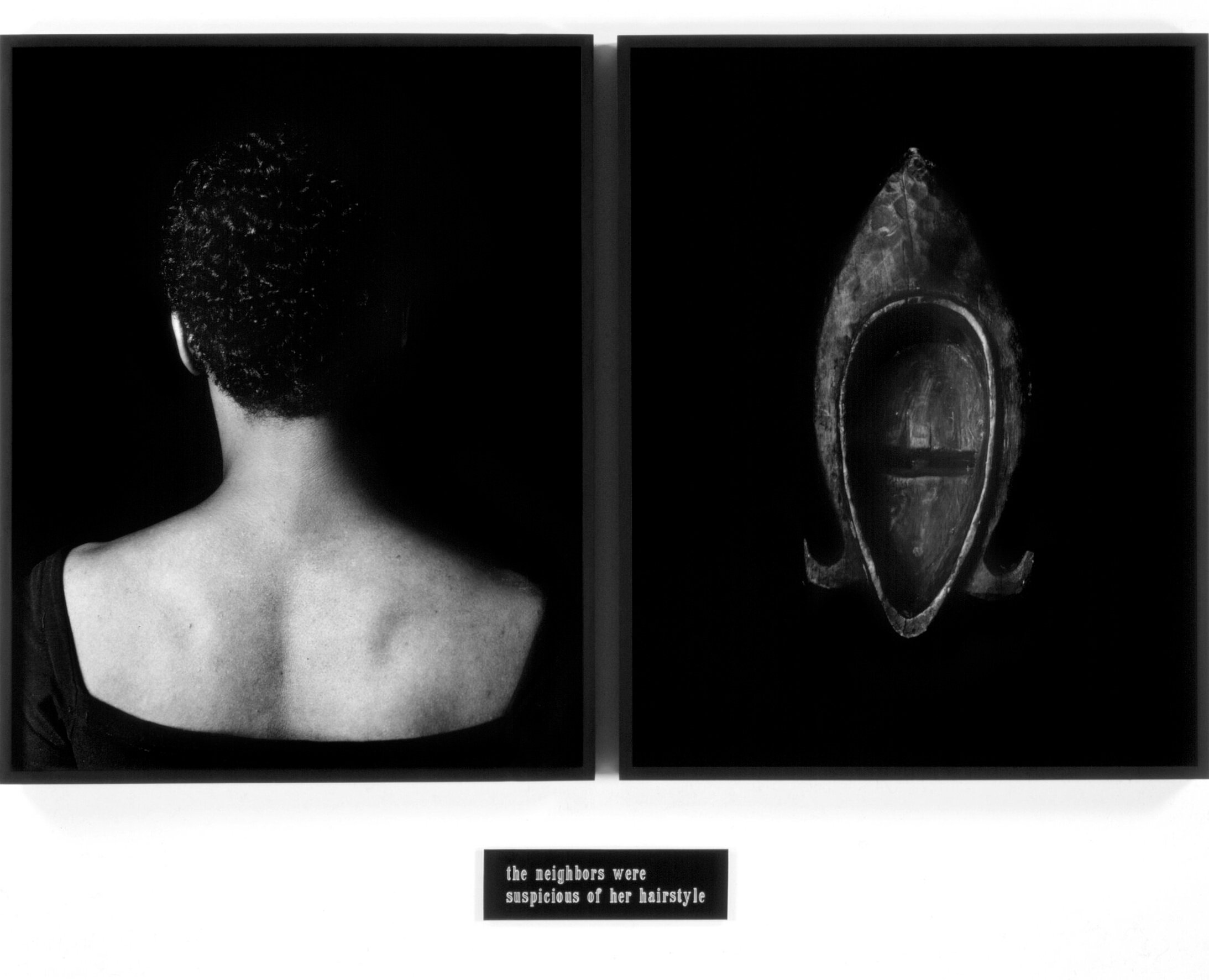

A significant moment of reckoning happened when I was studying Simpson’s Flipside, (1991), a stunning dyptych of black and white photographs whose left panel depicts an anonymous Black woman from behind–a gesture common in Simpson’s oeuvre. On the right side, is an African mask, a representation of traditional African culture, one that contributed and inspired the foundations of Modernism in the early 20th-century. It is also shown from behind. Its face invisible and in a very economical way, expressing the central issue of Black representation in America: that of (in)visibility–one artfully illuminated by writer Ralph Ellison in the early 1950s.

Simpson’s work often defies a singular meaning, but in zeroing in on the mask, I interpreted it as a mediating object standing between Blackness (the physical, intellectual and spiritual presence behind the mask), and a Eurocentric hegemony dominating the world of art and interpretations of the Black presence. In turning the mask around, Simpson was at least to me, subversively dismantling the gaze and exposing the presence behind it.

As a person living within the African diaspora and a student of contemporary art, I discovered I too had assumed the colonial gaze of the patriarchy by exclusively considering the mask from the front, damn! My true relationship and position to the mask, was actually authentically positioned from behind looking through it.

That revelation was so important to the trajectory of my studies and practice. It helped me to reposition myself appropriately within a proper relational geography to a Black-centered cosmology. That’s where I found my grounding and that’s where I have stood ever since. After that door opened, my studies fell so comfortably and easily in place. Many thank yous to Lorna!

1. We Who Wear the Mask: A Survey of African American Art Criticism and the Formation of an African American-centered Visual Theory from the Early 20th-Century to Post-Black.